An exhibition of the photographs of Alice Hunt

Dragon Hall, King Street, Norwich

5 – 26 March 2000

Alice Hunt (née Mortimore) was born on 4th February 1844 at Champion Hill near Camberwell, the eighth child of William and Harriet Mortimore. In 1870 she married Walter Freeman Hunt, a barrister who was related through his mother to the wealthy Seager family. Alice and Walter spent their early married life in Kensington where their first six children Ernest, Gilbert, Reginald, Donald, Ella and John were born. In 1880, the couple and their five surviving children, Ella having died in infancy, moved to Sedgeford in north-west Norfolk where they had acquired the lease of Sedgeford Hall from Eustace Neville Rolfe, a family friend and Donald’s godfather. Sedgeford is a comparatively large parish lying between Heacham and Docking. In 1883 it supported a population of some eight hundred people, most of whom were tied into a rural economy which was dominated by the large landholdings of the established Le Strange and Rolfe families. The Hunts remained in the parish until 1897, and it was there that their five younger children Gerald, Gertrude, Nona, Frank and Helen were born.

Alice’s earliest surviving photographs date from 1887, shortly before the death of her eldest son from influenza whilst at Eton. Her interest was maintained for almost two decades. Some 650 half and quarter plate glass negatives survive, as well as both mounted and loose prints of her work which are contained in various family albums. The bulk of these were taken whilst the young family lived at Sedgeford, a far smaller number being taken after they moved to ‘Hart Hill’ in Woking, and a handful relating to their residence in Folkestone where they leased a house during Walter’s final illness.

The Exhibition Plates

The photographs in this exhibition were taken when the Hunt family lived at Sedgeford. They are broadly representative of the subjects which were captured by Alice’s lens during this time. The images were divided into seven groups, illustrative of recurrent themes in Alice’s work. Individuals with a familial or professional relationship to the photographs were asked to comment upon an image from each section. The exhibition aims to illustrate the range of different meanings which are attached to the photographic image, to examine the extent to which the viewer refers to individual experience in understanding what they see. Although the caption writers were chosen because of a prior connection to the photographs or to photography in general, they do not hold a monopoly upon interpretation. It is the initial reactions, whether of heart or mind, which are evoked through the dialogue with these images with which we are interested. This catalogue provides additional biographical and analytical material which is intended as a supplement to these responses.

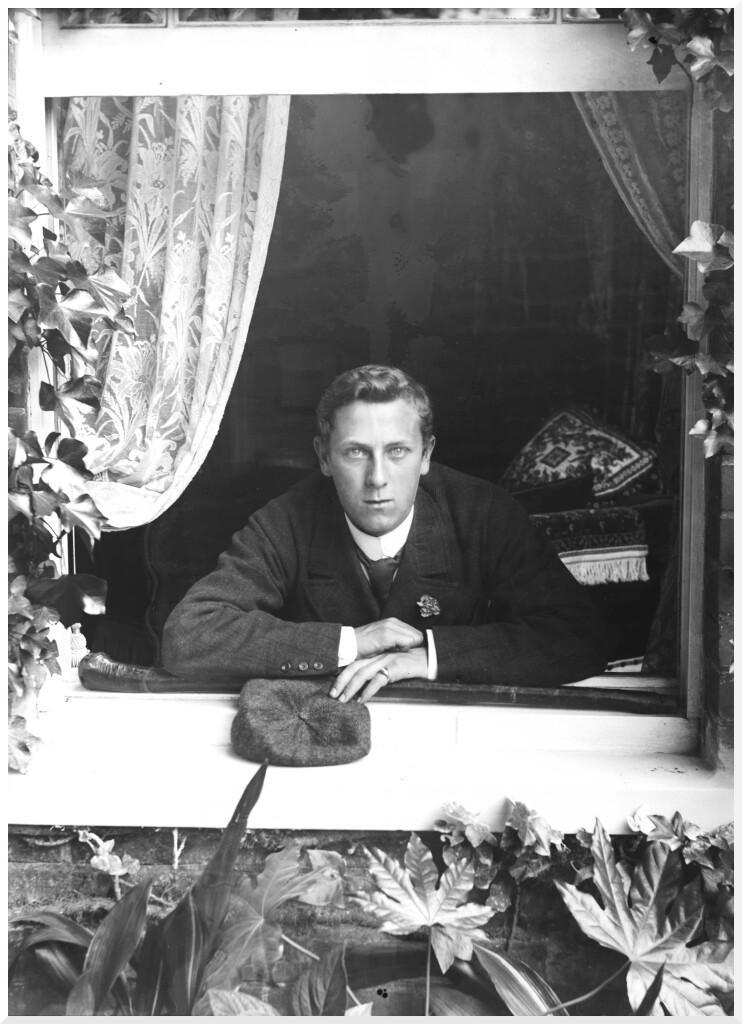

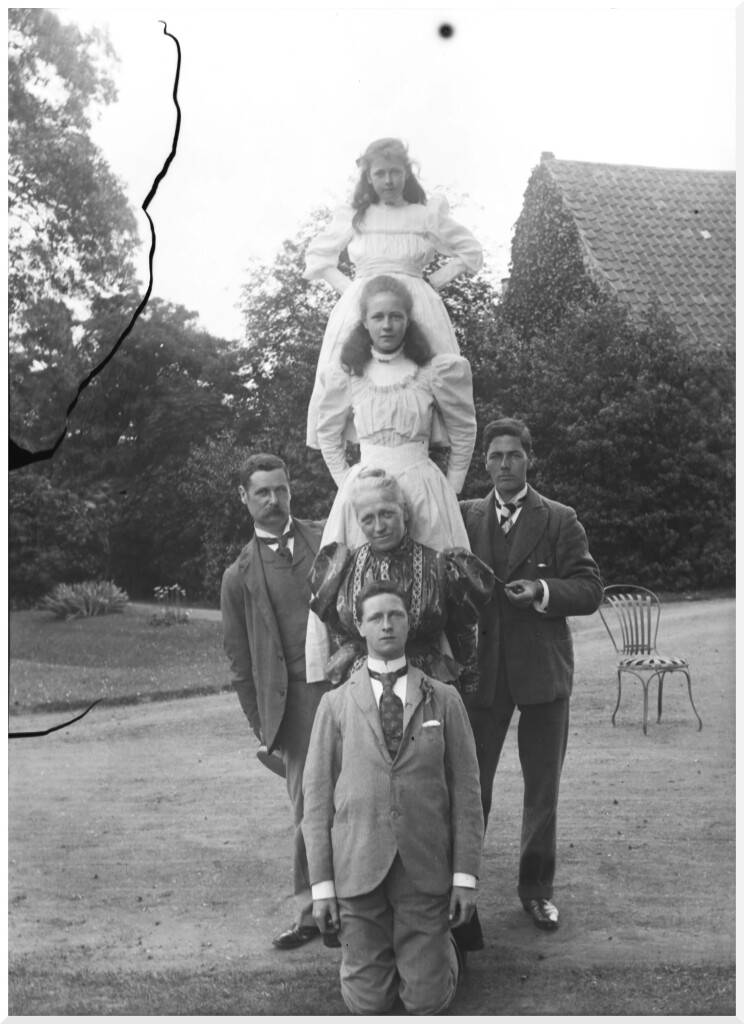

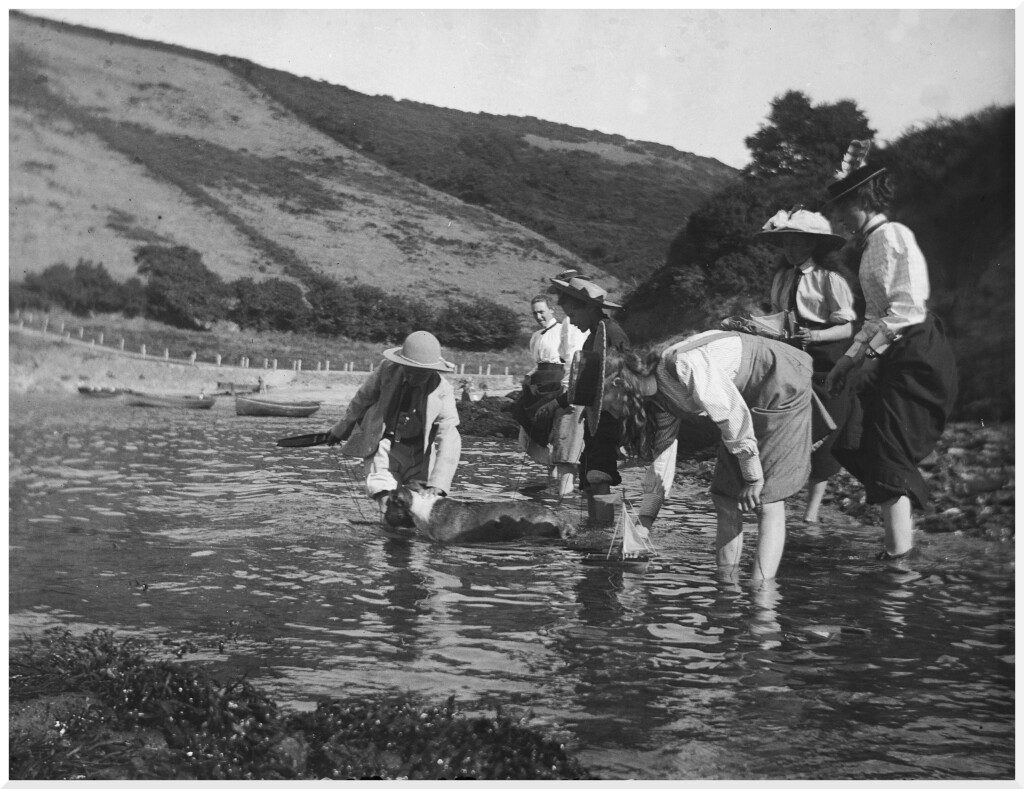

Alice’s sons enjoyed the upbringing which was expected of young men of their class during the late Victorian period. The eldest two sons were sent to Eton, the younger ones to Haileybury. The photographs that Alice took during their holidays suggests a range of suitably active pursuits. They are depicted playing cricket and golf, out shooting with the dogs, and dressed in cadet corps and militia uniforms. The sons’ chosen careers also involved a range of occupations fitting for children brought up in a British Empire whose interests were global. Gilbert went into colonial service in British Central Africa, where he died in 1898, Donald and Reggie joined the Army, and served with distinction throughout the Empire and in the Great War, John was engaged in scientific research in the Balkans, and Gerald left the London and Westminster Bank to manage plantations in Ceylon. Frank, the youngest son, went into the Church.

However, photographs of the boys do not merely reflect familial and socio-cultural expectations. They were informed by the tapestry of relationships and roles which makes up a family, and Alice’s photography conveyed a distinct personality upon each of her seven boys: responsible, confident Gilbert, sensitive Reggie, reflective Donald, scholarly John.

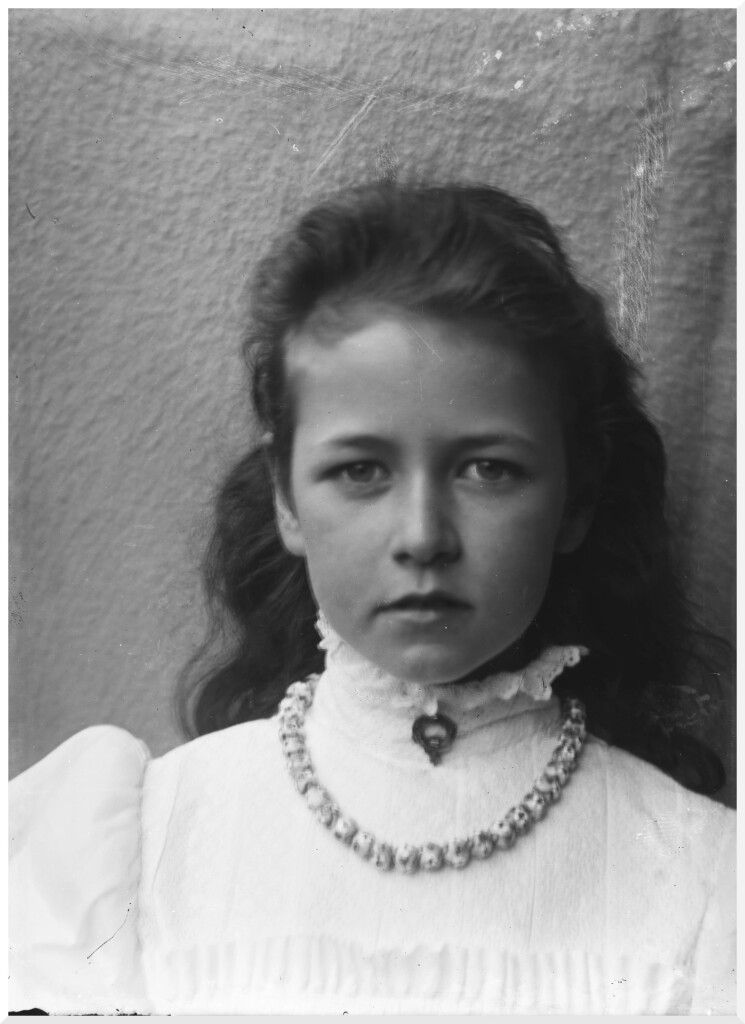

This image is the closest that Alice gets to what we may interpret as sentimentality in her depictions of her daughters. At a time when the new popular photography magazines such as Amateur Photographer were urging women towards ‘home portraiture’, Alice seems to be at pain to avoid any whimsical or overtly pictorialist approach.

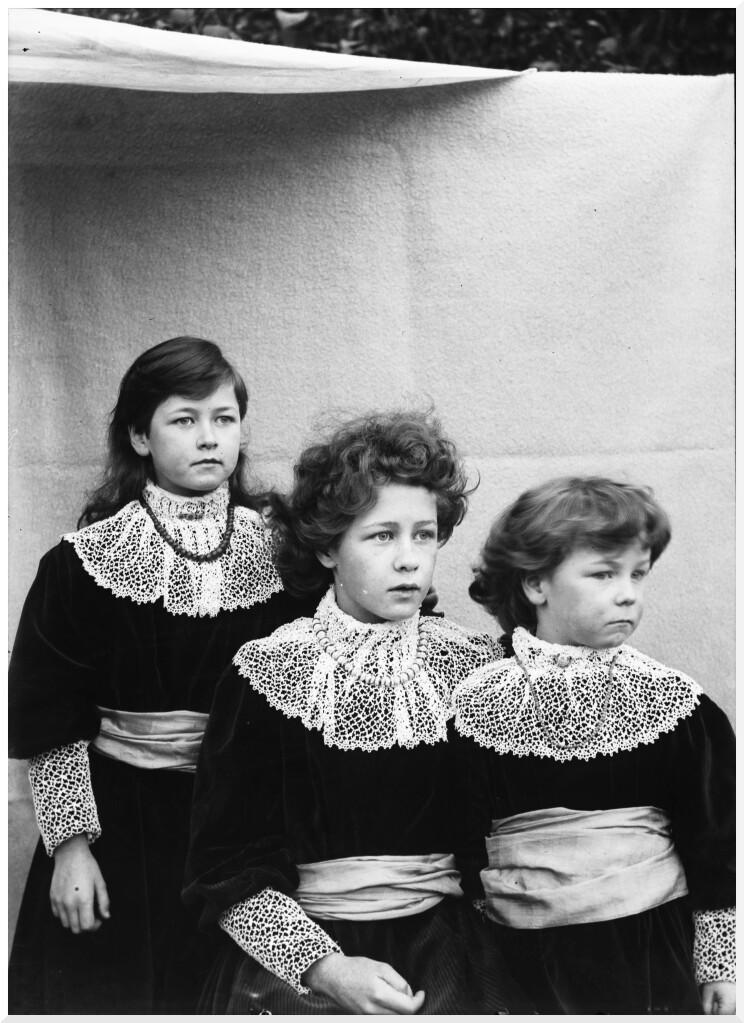

The three girls, all born within five years of each other, were educated at home by a governess, Miss Buckhurst, though Helen later attended a school whilst the family lived in Folkestone. As was usual for sisters during the late Victorian period the girls appear in identical outfits; ones which were even adapted to suit both Gertie as a young woman, in longer skirts, and her younger sisters, whilst maintaining a regimented appearance. This uniformity was informed by broader conventions; the girls are spoken of collectively in family correspondence: ‘the three little girls’ as Gilbert calls them in a letter of 1898. They seldom appear to express individuality within the images; they are seen most often grouped together, or with other family members, the passive subjects of their mother’s lens.

However, the contrast which could be drawn between active, individual sons and passive, homogeneous daughters may easily be overstated, for Gertie, Nona and Helen’s youngest brother, Frank, appeared in many of the photographs along side his sisters engaged in the same genteel pursuits. Gender differences were clearly present but may have been exaggerated by the life-cycle of the family which saw the sons growing to young men at the very time at which Alice was most prolific with her camera. When the time the girls were of a comparable age, the family had moved from Norfolk and Alice appears to have devoted less and less time to photography in general and portraiture in particular.

The vocabulary of posing for photographs is not innate, it has to be learnt by the subjects. In this photograph there is a clear distinction between the relaxed responses of Alice’s three children (the three central characters) to the camera and the wooden poses of the other children.

These images of an idyllic rural childhood represent only one aspect of her childrens’ experience. The boys who add such a vibrant dimension to all of Alice’s photography were away at boarding school or college for considerable parts of the year. Although Alice was a keen photographer, the majority of her work was taken during a ‘photographic calendar’ occasioned by school holidays, the visits of family and friends, or the return of sons from overseas.

As a collection, the photographs offer an insight into the leisured lifestyle associated with ‘society’ of the late nineteenth century: tennis parties, cricket matches between the villages of Sedgeford and Heacham, riding, ‘cycling mania’, the boys in ‘high spirits” with their close friends, picnics on the beach at Hunstanton. This is essentially the photography of the family, a record of togetherness and carefree times. In this respect Alice’s work, her instinctive understanding of the subjects for her camera, is a direct ancestor of the modern family photograph.

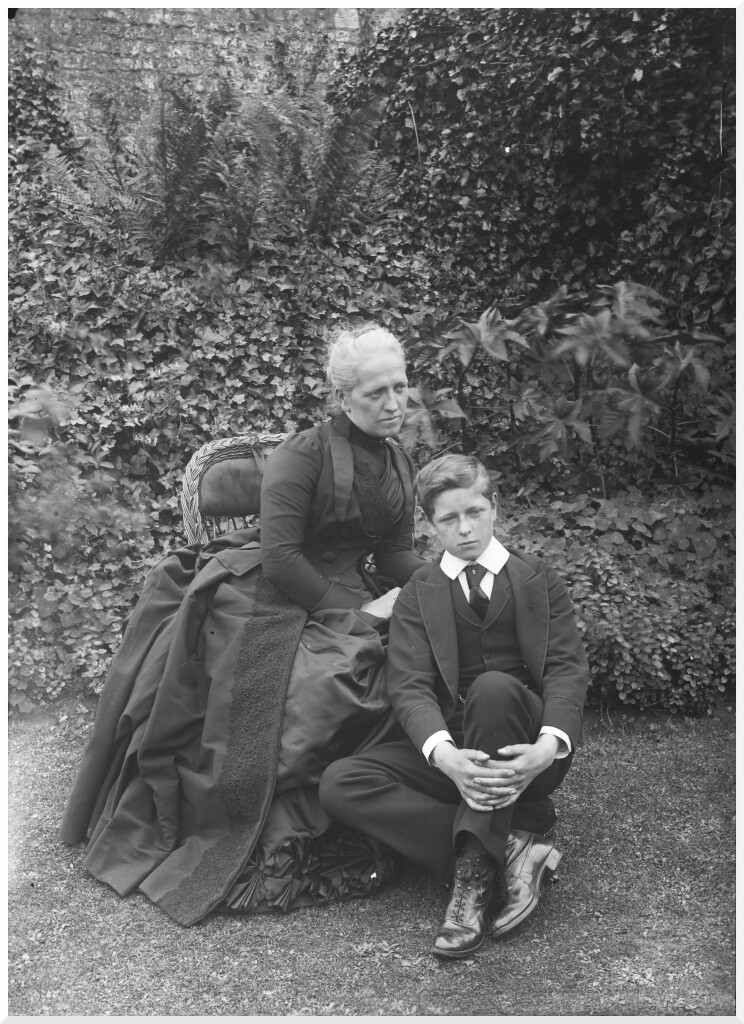

At first sight these family groups suggest the formality of late Victorian society. However, although ‘father’s’ natural reticence in front of the lens seems clear enough, a closer inspection suggests affection in the disposition and proximity between the sitters. Although separated by many years, the elder brothers and younger sisters are clearly relaxed in each other’s company; a closeness which is illustrated in a wealth of chatty correspondence between siblings.

These images illustrate the development of compositional sophistication as Alice learnt that photography is far more than a technical process. Nonetheless, she was not aided by either materials or environment. The comparative bulkiness of camera and tripod, relatively slow shutter speeds, conventions of posing derived from portraiture, and the limited patience of her young subjects resulted in a wide range of outcomes. Whilst one plate may appear strangely stilted, the next may be disarmingly modern and relaxed.

The influence of the technical characteristics of equipment upon Alice’s photographs may be deduced from a comparison between the images taken on half-plates and those on quarter-plates. The latter unrestricted by weight of apparatus, introduce an air of informality and display an idiosyncratic approach to composition. This contrasts with the half plates, over which far more care had to be taken. The quarter-plates are illustrative of Alice’s desire to capture a moment in time, reminiscent of the ‘snap-shot’ of today (Plate 6). When she attempted this with her half-plate camera the quality of the image improved correspondingly, but this could be at the expense of the ‘moment’.

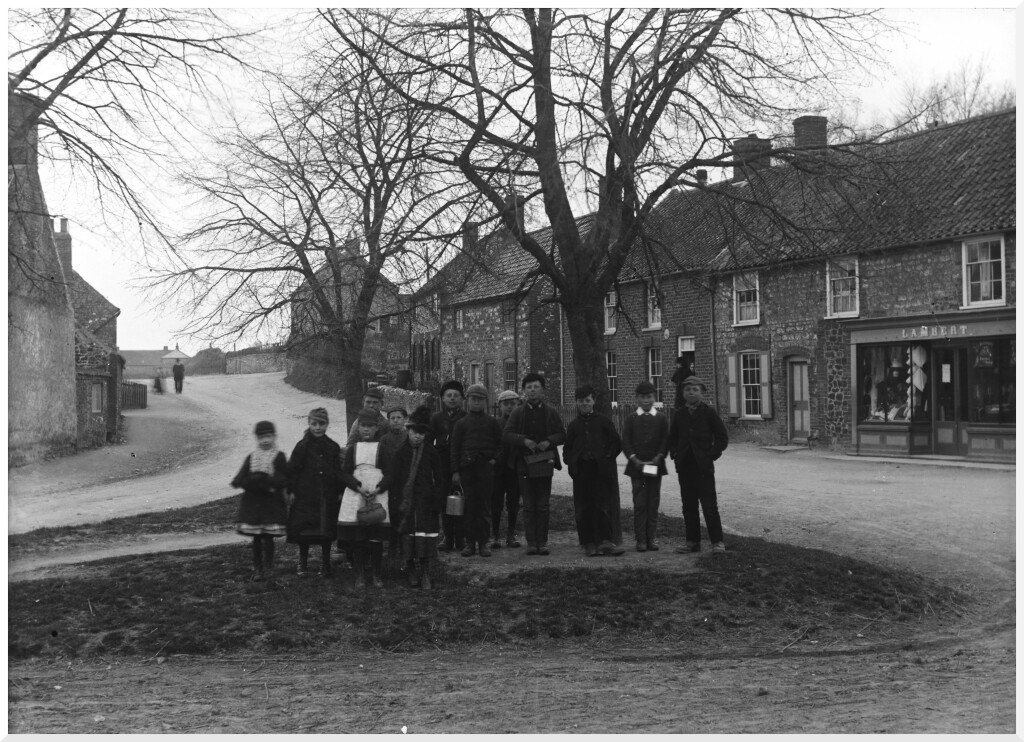

The Hunt family were newcomers to Sedgeford. Although they took on the lease of the Hall there is little to suggest that they had close ties with the landed gentry in the area during their residence and the friends who appear in her photographs seem to have been drawn mainly from the local clergy and professional classes.

Alice’s pictures of local characters and rural activities are indicative of an understanding that the Hunts were temporary residents within the parish. These photographs sustain the social distance between subject and photographer but there is no suspicion of the deferential demeanour which could accompany those ties of patronage enjoyed by the landed gentry. Alice’s subjects did not interpret social distance as social inferiority.

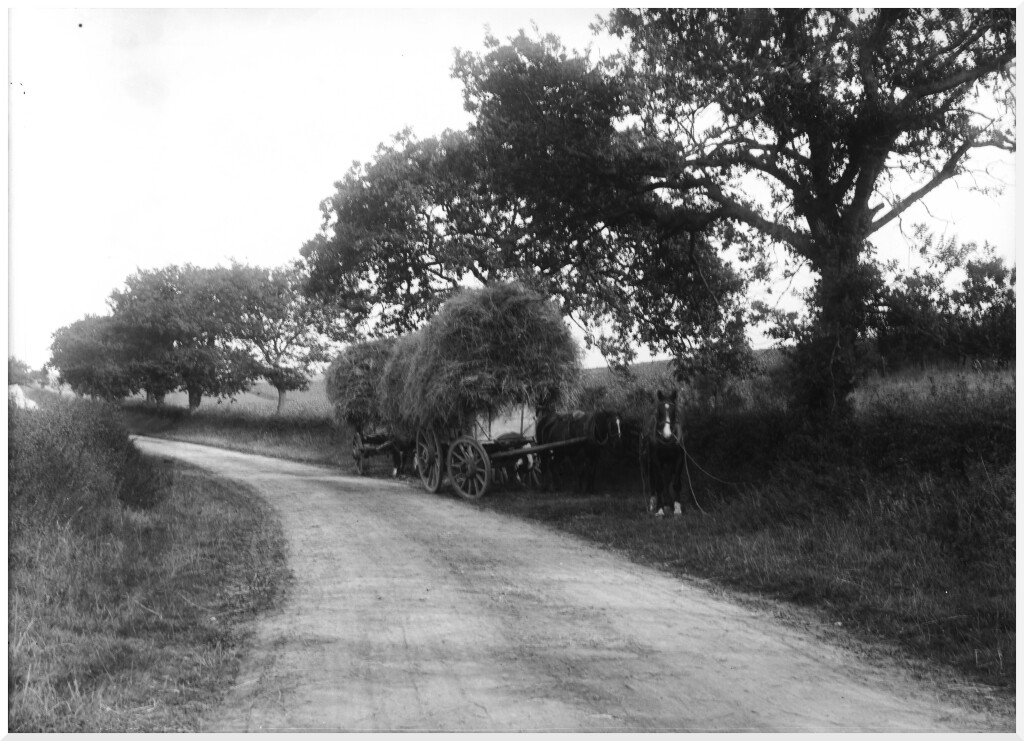

These are not photographs taken to document rural conditions or to record a way of life under threat. The number and range of subjects is simply insufficient to this to have been Alice’s intent. These were images captured by an enthusiastic amateur as and when occasion arose and circumstances allowed; be it the presence of harvest machines near the Hall, the arrival of charcoal burners in the parish or meeting a local basket-maker in the lane.

Although the most of Alice’s work related to her family, she also had a strong interest in photographing landscapes and buildings. Almost all of this seems to have been carried out in that corner of West Norfolk bounded by Docking, Hunstanton and Snettisham. The series of landscapes entitled Views about the County contains her strongest work, but there are also a substantial number of images of both the interiors and exteriors or local churches.

As was the case with her photographs of rural life, these are images taken by Alice as she travelled by horse and carriage throughout the area. Their quality varies considerably, as must have the leisure with which she had to compose them. They fit into a landscape tradition which was well established by this time and is frequently seen in the photographic albums of other dry-plate enthusiasts.

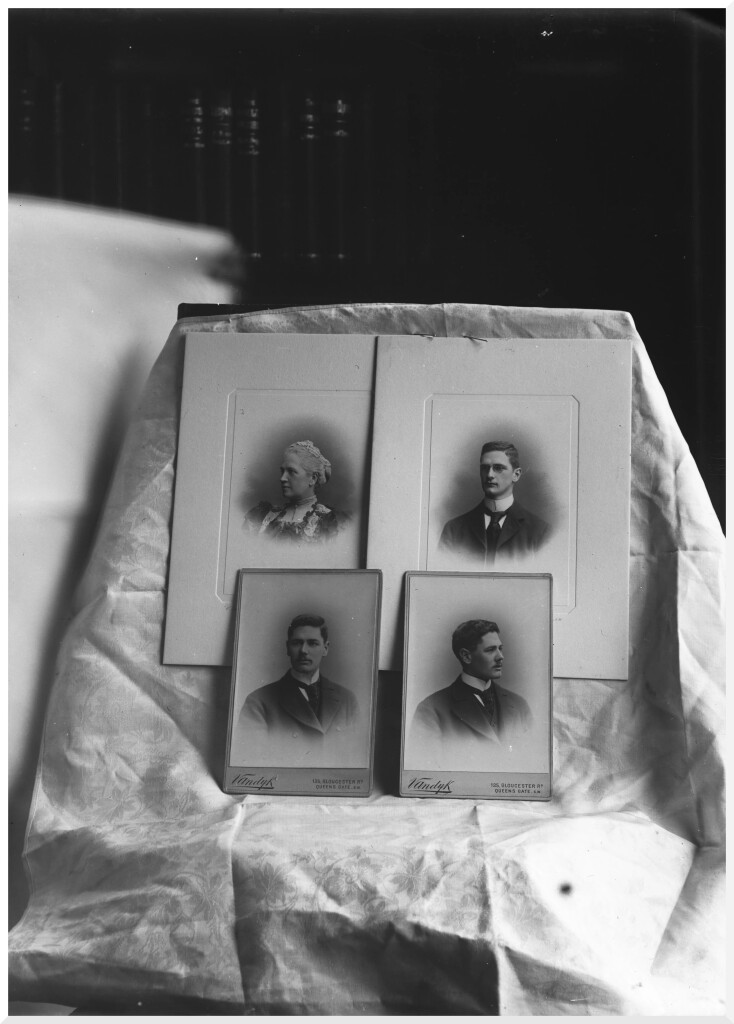

The family paid regular visits to Vandyk’s photographic studios in Kensington and inside her home Alice used studio portraits in a variety of frames to complement a stock of family paintings including portraits in pastel and silhouette. Alice’s own pictures of domestic interiors show the great importance which such photographs played in the ‘family art’ tradition of home-making. She also took her own photographs of these portraits and vignettes, arranging images of family members in a series of different relationships to each other. In doing so she contributed to the process of re-ordering and editing by which such images are reconstituted anew to be bequeathed to the next generation, and through which the concept of the Family retains Its vitality.

This process of ordering was also undertaken in family photograph albums. Despite the importance of family portraits, we rarely see examples of her own photographs on show in the house. Prints of Alice’s work were kept in albums. These albums were effortlessly incorporated into the ‘upper class folk art’ tradition which women of Alice’s class had inherited from the household books and autograph albums of their pre-photographic sisters. A number still survive in family hands some containing studio portraits of family members dating back to the 1850s, and some including examples of her own work augmented by later additions taken by her children.

Alice’s photographs were more than just a means through which family could be bequeathed from one generation to the next, they were also a vital means of communication between separated family members. A parcel of photographs returned after Gilbert’s death from blackwater fever in British Central Africa in 1898, included images of the new family home, Hart Hill, in Surrey. On the back of these were annotations in Alice’s hand relating to its features and layout. After Donald’s death in 1949 a small package marked ‘Donald’s photo’s of home, sent home by Grizel (his wife)’ was sent back to Norfolk to Gertie from South Africa. It contained a heavily-thumbed selection of Alice’s Sedgeford prints, wistfully captioned and kept by Donald all his life.

End Words

To view a set of photographs like those taken by Alice Hunt is to invite the observer to ponder upon image, an elusive will-o’-the-wisp which inhabits a myriad of different realities and lures us down many uncertain paths.

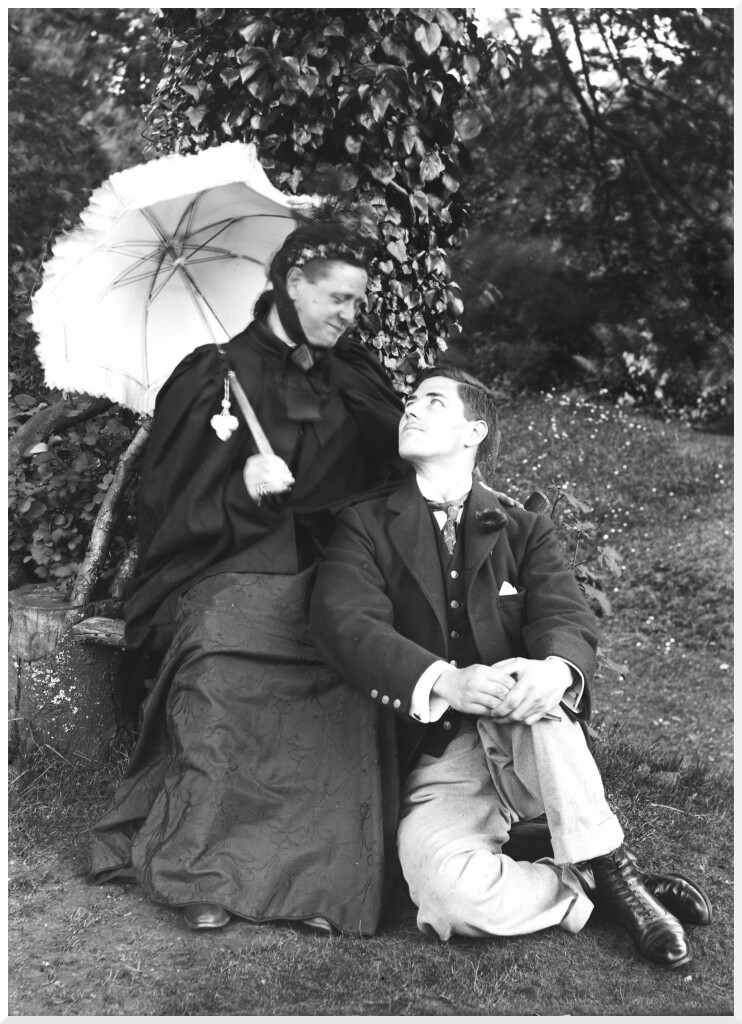

If there is a truth in our response to these pictures it is one which belongs to us alone. By the same token the world in which they were taken is now locked away forever. What we may guess about Alice both from her self portraits and from her portrayal of her nearest and dearest is confirmed by her grandchildren. She was a matriarch of dignity and stature; a resilient person who found a way of dealing with personal tragedies, and a formal woman with a great sense of propriety. But we should be wary of speculating upon something as ill-defined, dynamic and variable as family relationships. We may discover that the sweet girl cuddling her pet actually detested cats, or that the ‘adoring mother’ is in fact Reggie in disguise (Plate 10)…

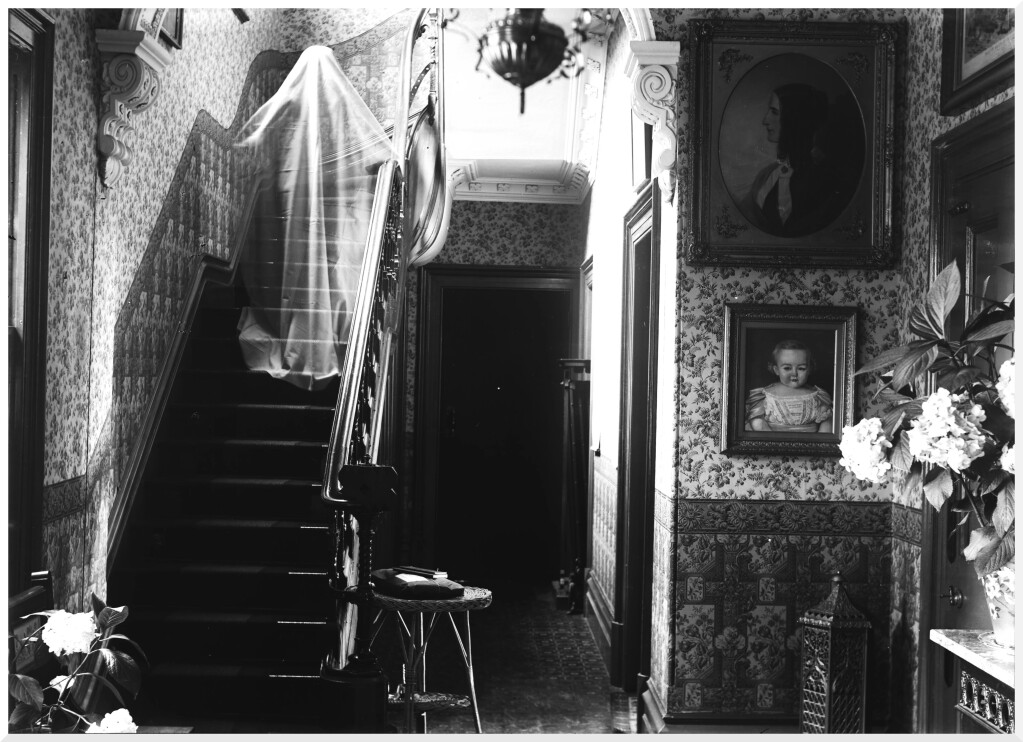

but we will never know who or what occasioned the appearance of the spectre on the stairs (Plate 11).

A further discussion of the work of Alice Hunt is included in Second Sight, no 14, Spring 2000, pps 16-22

Credits

With many thanks to the relatives of Alice Hunt for their patience, encouragement and help in realising this exhibition and to the Centre of East Anglian Studies, University of East Anglia, for its initial support

Optical Allusions Festival

A Moment in Time design Dick Malt

Exhibition photography Cliff Middleton

Hosts Dragon Hall, King Street, Norwich

Catalogue text © Jan Pitman & Cathy Terry, March 2000

Print Witley Press, Hunstanton

button in the top right of the map display to select which years to display.

button in the top right of the map display to select which years to display.