The Alice Hunt Collection

by

Cathy Terry and Jan Pitman

Collections of family photographs are inevitably viewed from an individual perspective. Our knowledge of the subjects, the events in which they participate, or the social groupings that we suppose them to belong to, all colour our responses to a picture. Nonetheless, viewing is not necessarily an entirely solitary experience since these responses may be filtered through an ill-defined complex of socio-cultural understandings by which a photograph may become part of a shared past.

This is particularly true of early photography. Images of Victorian and Edwardian Britain are placed in a very particular historical context: the possession of an empire whose decline was barely conceived of, the supposed presence of a value-system which has become so important to contemporary political rhetoric, and above all the spectre of total war into which those photographed were unwittingly to stray. Our understanding of this context as a part of our own history allows the unknown pasts of those who are viewed to become transformed into quasi-communal possessions by which means they may stand for those of our own ancestors – one of the reasons why, amongst the horse-brasses and toby jugs, such photographs adorn the walls of countless public houses throughout the country.

This process relies upon us appropriating these images as our own. It raises the question of the degree to which our responses change when a two-dimensional subject becomes fleshed out by biographical information. This is one of a number of issues which were raised by the study of the photographs of Alice Hunt, a woman photographer active from the 1880s until the early twentieth century.

The collection first came to our attention as a potential source for general social history since it included a sizeable number of images of places and people from around the county of Norfolk. However, it quickly became clear that it had a greater importance. These photographs were taken during the first years of popular photography heralded by the dry-plate process which made it relatively straightforward for the enthusiastic amateur to produce good results. Nonetheless, collections of family, rather than trade or documentary photographs from this period are rare and it goes without saying that those of a female photographer are more so. Such an archive lends itself to many different avenues of enquiry which we cannot do justice to in a short article.

Therefore, we will restrict ourselves to an overview of the collection and focus upon certain general issues arising from the process of research.

In total over four hundred half-plate and one hundred and twenty quarter-plate photographs have survived. These appear in an unedited fashion and both unsuccessful photographs and those where two identical pictures were taken have been retained. Although we cannot be sure that the collection is complete, it seems reasonable to assume that the photographs offer a comprehensive sample of those which were actually taken.

The great majority of the plates were taken in the parish of Sedgeford in north-west Norfolk. Alice and her husband Walter moved to the parish from Kensington in 1880. They took with them their five young children; Ernest, Gilbert, Reggie, Donald and John, and a further five; Gerald, Gertie Nona, Frank and Helen were to be born there during the next eight years (see plate 1). Walter was a barrister by profession but by the time of the move he appears to have been in at least semi-retirement, perhaps due to ill-health. The family was a wealthy one Walter was related to the Seager family who produced a gin of the same name. In 1880 he acquired the lease of Sedgeford Hall from Eustace Neville Rolfe, his friend and Donalds godfather, who had temporarily relocated to Naples in 1879 as a result of financial diffculties brought on as a result of agricultural depression.

A more limited number of plates relate to Hart Hill in Woking, a house which the family purchased in 1897. After five years residence the house was leased out and Walter, Alice and the younger children moved to Folkestone as a result of Walter’s declining health. It was there that he died in August 1903. Alice took a handful of photographs whilst in Folkestone but, following her husband’s death and as her family grew-up, her interest in photography appears to have waned,

On the whole, the photographs are well-taken. Alice took care over exposures and focusing and, although the majority of the pictures were taken outdoors, she was sufficiently involved to experiment with combinations of flash and ambient light on interior shots. She also attempted multiple exposures. and produced a successful ‘ghost’ picture on the staircase at Hart Hill. However, this did not translate, into a pedantic attention to the finer details of each picture. As one would expect with moderately long exposure times and a young family, blur was not uncommon but this was not of sufficient concern for such plates to be removed from the collection.

The photographs dealt with a variety of subjects. Alice took her camera with her on travels around the county and a considerable number of pictures of churches and views have survived. These are of variable quality, ranging from those where the camera was not horizontal or where the subject was lost amidst an abundance of detail, to some well-composed church interiors and a picture of the steps of Castle Rising keep which may have been derived from that of Wells chapter house by Fox Talbot. These images are those taken whilst in company rather than those of the lone and dedicated photographer. In some cases Alice was able to take a carefully considered picture, whilst other circumstances did not allow such leisure.

Alice Hunt was also concerned to record something of life in and around Sedgeford. The individuals who plied their trades throughout north-west Norfolk such as the basket-maker and tinker were subjected to her lens, as were school children from Sedgeford school, mothers ‘sticking’ and other local ‘characters’ (see plate 2). For the most part these photographs are both static and uncomfortable, with the subjects staring uncompromisingly into the camera. Alice may have had the interest and perseverance to set up her tripod and obtain a still subject, but many of these photographs were taken at a distance which suggests a certain reticence. There is little posed about these images and the impression given is one of chance meetings in the lanes of Sedgeford rather than of any more coherent design.

These pictures of Victorian Norfolk are of considerable interest, but the primary function of Alice’s photography was no documentary, It is images of her family and friends which form the bulk of the collection. With the exception of a handful of interiors and pictures taken in the conservatory, these relate to a sociable extra-mural existence in which, apart from the occasional bad winter during which the children built a ‘snow sphinx’, the sun was usually shining.

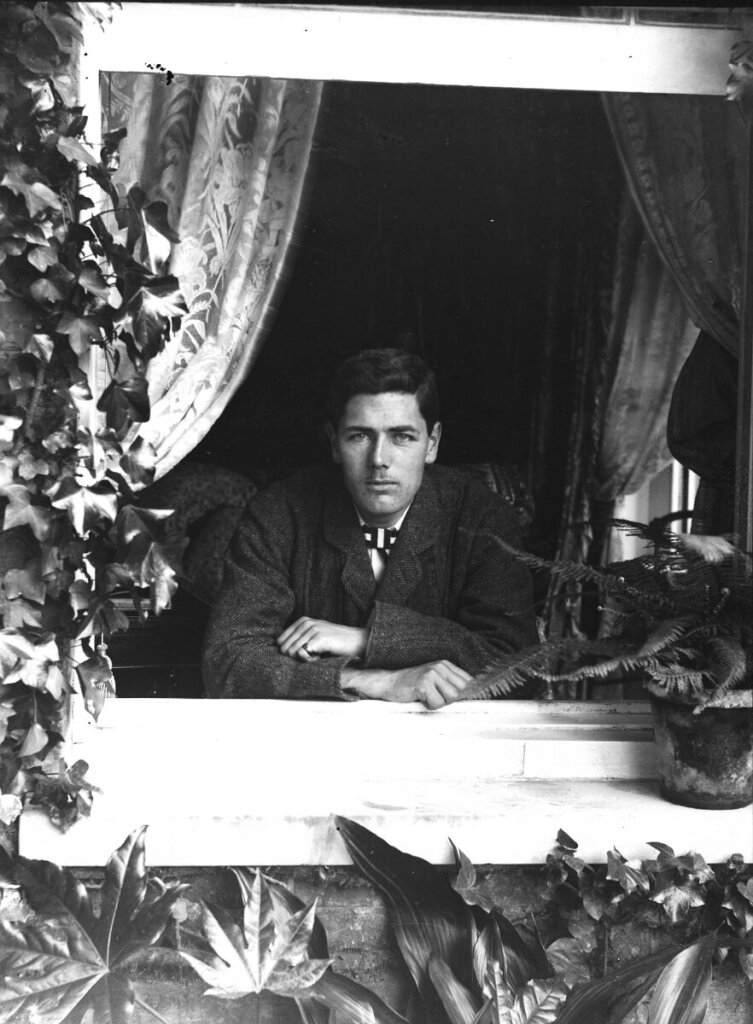

Many of these images are semi-formal individual portraits. The subjects stand or sit, and stare unblinkingly into the camera towards an illusory off-centre object, or at a simple prop such as a book (see plate 3). These compositions are the work of studio photographers, relating to a conventional set of expectations as to how memory and family should be structured. Although the detachment and dignity often associated with certain social groupings during the Victorian period appear to be their watch words, these also relate to a tradition of portraiture which both pre-dated photography and is very much alive today This is the sitter as an ideal, a subject removed from the viewer by which process of removal some aspect of the inner-self may be revealed. With respect to the family itself these portraits may also relate to concepts of lineage. and through such conventions the generations may be displayed and viewed as part of a continuum.

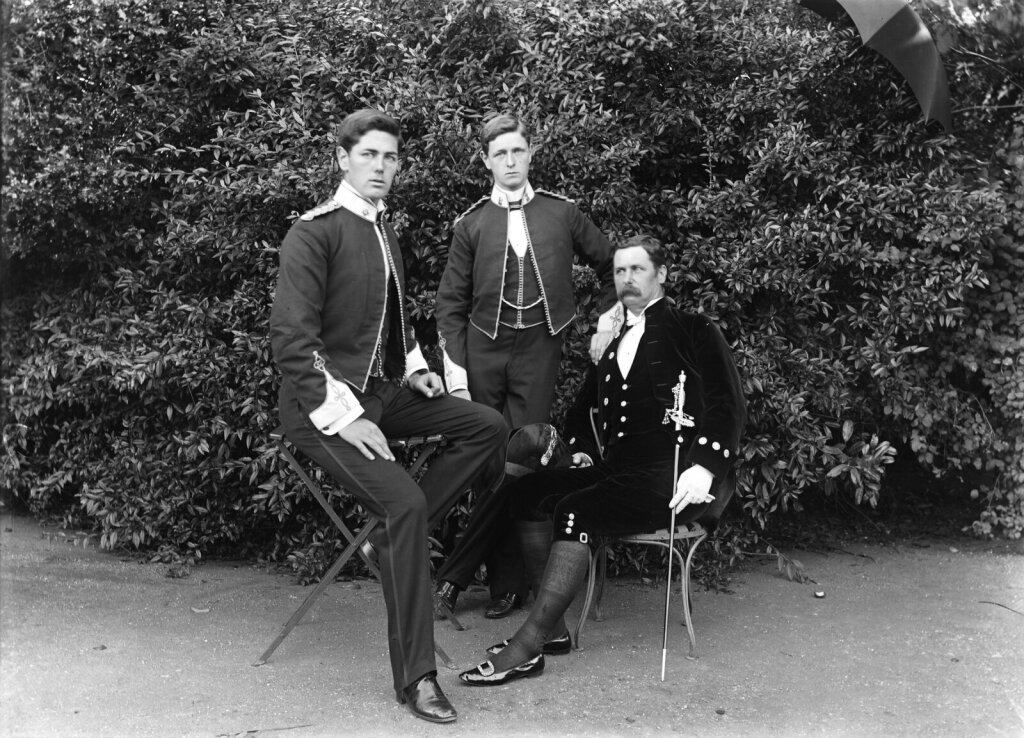

Service to one’s country was important to the Hunt family. The sons were educated at Eton and Haileybury and of the six who survived to adulthood, Reggie and Donald served overseas with the army, whilst Gilbert joined the colonial administrator. Both John and Gerald also worked abroad; John was involved in scientific research connected to the tanning industry in Hungary, Borneo and what is now Turkey, and Gerald was concerned with financial aspects of tea and rubber planting in Ceylon. Only Frank who joined the clergy, resided in Britain throughout his life. A number of group portraits such as that of Walter in court dress and Reggie and Gilbert in uniform may be illustrative of the aspirations, achievements and duties of the family (see plate 4).

However, although these images may have had such connotations, it is important to exercise caution with such interpretations. They may form an extremely partial understanding of the collection which fails to recognise that the distance and formality which underpins our reading of early photography may be as much a result of technical limitations as cultural convention. At first sight a picture of Walter and Nona offers just such an impression, the rigidity of posture and expression echoes stereotypical Victorian values (see plate 5). On closer inspection, however, the unrelaxed attitudes are belied by the images’ composition; Walter with boater and cane, Nona with her hand on his knee, the dog asleep on the grass at their feet.

This contradiction between the initial appearance and constituent elements of many images is emphasised by the humour which runs through the collection. A photograph of the ‘son’ staring adoringly at his ‘mother’ is inverted when we realise that as is Gilbert and Reggie caricaturing the over-sentimentality of much contemporary family portraiture. A series of photographs taken with various members of the family supporting each other with a ladder achieve a result which is bordering on the bizarre (see plate 6) whilst the image of a recumbent family friend with empty bottle in close proximity and the chalk slogan ‘hic jacet Palmerius – mostly hic’ tells its story.

It is in the comparison of the quarter-plate photographs with half-plates that the influence of technical restrictions upon the s is made clear. The quarter-plates, mostly taken whilst the family was on holiday, are those of any family holiday, they are no longer posed and smiles begin to appear. With a lighter camera a tripod was no longer necessary and as a result the composition of these pictures frequently declined, to become snap-shots of family dynamics which we immediately recognise today (see plate 7)

It is in this light that we must interpret a large number of half-plate photographs which show Alice’s children engaged in a range of different activities; playing in the snow or the sand-pit, the girls about to leave on bicycle rides, the boys off hunting or playing golf (see plate 8). If these are frequently as static and distanced as the more formal portraits it is important to appreciate that Alice was restricted by the length of time that her children would tolerate her attentions, Indeed on occasion it may not be fanciful to identify barely concealed rebellion in their faces. These photographs are essentially snap-shots taken with equipment was barely capable of fulfilling such a role. Attempts to record the children in a naturalistic way were hampered by exposure times and cumbersome equipment.

The Alice Hunt collection is important because it enables us to compare two different formats and a range of subjects. In doing so it becomes clear that, in viewing any individual photograph, the relative influences of the intent and ability of the photographer, the circumstances under which a photograph was taken and the technical limitations of the equipment are extremely difficult to disentangle. It becomes clear also that if every picture tells a story, it is only a partial one.

Where circumstances allowed, Alice was capable of taking photographs of considerable sensitivity and affection, such as those of her young family on the lawn (see plate 1) or of Gertie and Nona in the hammock-chair. However, the point is that it was not always possible for Alice to obtain these results. She had to work around a young family whose patience and ability to remain inactive were by no means inexhaustible.

From the outset of popular photography the camera performed a range of different roles. It was employed to record the family in a semi-formal tradition of portraiture, and as a testament to it during the ‘good’ times and at play. As is common today, these images were an important means of communication. They may have served this function with respect to a range of relatives, but it is as Alice’s older children moved overseas that we see explicit examples of their use to transmit visual information relating to the family and its surroundings

If the family were the prime focus of Alice’s attention, the camera also fulfilled other functions. It allowed artistic inclinations to be expressed in views and landscapes, and appears to have encouraged a vague feeling that certain local events and characters should be preserved for posterity.

In both the subjects which she took and the restrictions upon this activity it is possible to see Alice Hunt as the direct ancestor of the enthusiastic amateur of today. It goes without saying that the world the Hunt family inhabited was very different to that of today, and their pre-conceptions and values were therefore very different. Nonetheless, despite these significant differences, Alice exploited the camera in way we can instinctively empathise with.

In this way these early photographs may become demystified: we are able to trace concerns which are not dissimilar to our own. However, if we are therefore brought closer to these images, the process of research also distances us from the subjects. In certain respects the impact of these photographs may be heightened by biographical information; of the deaths of the shy and retiring Walter, of Gilbert from malaria in British Central Africa in 1897 (see plate 3), and of the eldest son Ernest at Eton aged seventeen. On a happier note, we learn that all the children survived the Great War, Reggie and Donald serving on the western front where Reggie was awarded the D.S.O, and Gerald serving with distinction at Gallipoli.

The family history which we were able to develop is important in its own right, providing a detailed case-study of the concerns and dynamics of a specific social group. But in terms of our emotional response to the pictures, the façade of a shared past can no longer be maintained. These photographs belong to someone else’s history, they serve as a medium through which the past is understood. This is a history of Walter’s mother’s death of a seizure during the Indian Mutiny, of Reggie laid out to be buried with the dead but for a wagging finger during the Boer war, of Donald’s affection and respect for the people of Sekukuniland in South Africa, and of John ensuring the safety of his Greek employees before leaving Smyrma in a boat with muffled oars at the time of the Turkish take-over. It is a history over which we have no rights of possession

Research into the photographs of Alice Hunt was generously supported by the Centre of East Anglian Studies, University of East Anglia. An exhibition is planned as part of the forthcoming “Optical Allusions” festival. Jan Pitman and Cathy Terry would also like record their thanks to the many members of Alice Hunt’s family for their continued assistance and encouragement.

Cathy Terry

is a social history curator working for Norfolk Museums Service. She has compiled a data base of archive photographic collections in East Anglia and also devised the touring exhibition “Snapshots – the Story of Domestic Photography”.

Jan Pitman

has recently completed a Ph.D in History at the University of East Anglia. He now works as a freelance historical researcher.

This article was originally published in Second Sight No. 13 Spring/Summer 1999. Second Sight was a journal of photography by Richard Denyer and published by Half-Tone Press.

button in the top right of the map display to select which years to display.

button in the top right of the map display to select which years to display.